Academia: Essays #1

Secret Passages - exclusive content

§

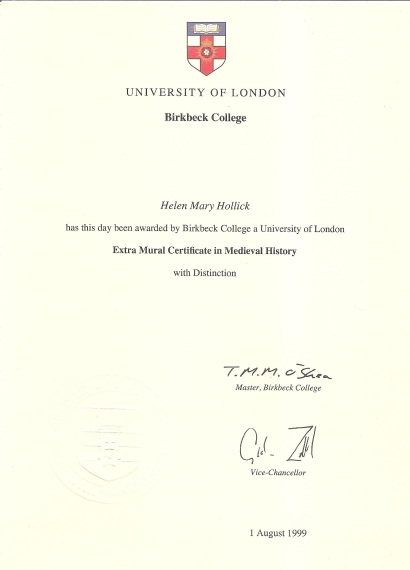

"Queen Emma is one of the great neglected figures in history. Discuss."

This is an essay, written in 1997 during the early part of a history degree course at Birkbeck College, University of London. It shows another aspect of the research required when preparing to write a historical novel. |

| Page 1 It could be tentatively argued that the first chapters of the Norman conquest of England began in the spring of 1002, with the marriage of Emma of Normandy to Æthelred, King of the English. Emma was a daughter of Richard of Normandy, great grandfather of William I of England, and sister to the ruling count, Richard II. Although of Scandinavian descent, the "Northmen" were, by the early eleventh century, mostly Christian and were rapidly becoming French. An alliance would prevent Vikings from using Norman ports from which to harass England. Henceforth, the Counts of Normandy would have a considerable interest in the English crown, with the ambition being that a son of Emma's would succeed to the throne. Two, Harthacnut and Edward, did rule, but both were childless, thus eliminating the prospect of Norman rule by direct succession. Considering that the alliance between Normandy and England was to bring security from Viking raiders, it is ironic that when Æthelred died in 1016, Emma then married one of the most prominent Vikings of this period, Cnut, who conquered England and became king. At the age of twelve, Æthelred had married Ælfgifu, a daughter of a northern earl, in order to win support. She was never consecrated as queen, for this position was taken by the already anointed Ælfthryth, her mother-in-law. The queen's duties were retained by Æthelred's mother until her death in 1002. Ælfgifu did not witness any royal documents, nor, it seems, was she responsible for the upbringing of her ten children. It was only after his mother's death that Æthelred took a second wife. It is unclear whether he had set Ælfgifu aside, or whether she had died; probably the latter. Emma, unlike her predecessor, was anointed and became a queen who was to eventually carve for herself a significant position within the political estate of England. Her first son, Edward, was born circa 1005, with a second son, Alfred, coming a year or so later. The succession to the throne however, was disrupted in 1013 by an invasion of Svein Forkbeard of Denmark and his son, Cnut. In the autumn, Emma and her sons, at her initiative, fled to Normandy, soon followed by Æthelred himself. Page 2 In the spring of 1014 Æthelred dispatched ambassadors to England, with his young son Edward, accompanying them, to negotiate a return to the English throne. Shortly after Æthelred's reinstatement, his son by Ælfgifu, Edmund Ironside, began to act independently of his father. Emma, it seems, was also dissatisfied with her husbands succession of ill-advised failures, for she transferred her support away from Æthelred, to Edmund. In the Encomium Emma Reginae, Æthelred is not merely omitted as her husband, but his existence is significantly suppressed. Emma was a strong and determined women who knew her own mind, what she wanted, and was ruthless in her ambition to obtain it. It is doubtful that she would have chosen to deliberately forget her first husband because of infidelity, more likely, she was dissatisfied with his many failures and his continuing weakness as a king.(1) Æthelred died in 1016, Edmund Ironside then occupied the throne and withstood Cnut, with the boy Edward, who was possibly no older than thirteen, at his side. That Emma had deliberately sent her eldest son to be with his half brother is not doubted, the opportunism would be typical of her character. Edward would have been too young to stand against Cnut on his own, her only chance of recovering her position, wealth, and estates, would have rested on Edmund's success - with Edward prominent as his successor. Unfortunately for Emma's calculated hopes, Edmund died on 30th November 1016, and effectively in possession of the country, Cnut became king of England. Danish kings would more commonly take wives near to home, yet Cnut contracted a marriage to Ælfgifu of Northampton; she was from a north Midlands family from which Edmund Ironside had also hoped to gain support. When he became king, Cnut turned to securing his position more positively, and took Emma as his second wife, in July 1017. Cnut had a reputation connected with paganism, and badly needed to establish his devotion to Christianity. The degree of involvement that Emma herself had in the betrothal negotiations is unknown, but she was certainly a shrewd, and politically, a wise woman. She was the legitimate and consecrated queen of England, could bring Cnut into alliance with Normandy, and provide the edge of respectability that he sought. As Queen, Emma had acquired expertise in English politics, an expertise Cnut could use. In addition, a king's widow, and her kin, were the obvious supporters of sons who could raise a challenge to a new king; marriage to Emma diverted support away from the two royal English sons, and neutralized any potential opponents. The Widow could carry substantial influence, and could be in possession of considerable wealth. 'The master plan of the sixth or seventh century usurper had three stages. Murder the king, get the gold, marry the widow. Since the widow usually sat on the gold, the two went together.(2) 1) F. Barlow : Edward the Confessor p.35 2) P. Stafford: Queens Concubines & Dowagers p.50 Page 3 Emma achieved a position of prominence under Cnut that she had not enjoyed under Æthelred. She benefitted from her second husband's control of three kingdoms and from his absences in Scandinavia. Cnut had not set his first wife, Ælfgifu, aside, but had set her as regent of Norway, it seems probable that he gave similar powers to Emma in England. Cnut had control of a vast territory, which included at times, in addition to England, Denmark, Norway and parts of Sweden, the Viking colonies of the Isle of Man, the Scottish isles, and Ireland. He frequently needed to leave England. With Emma as Regent, the Country would remain secure. The marriage, however, created conflicting loyalties regarding the succession, for Emma and Cnut both had sons by previous marriage - Emma's Edward and Alfred, Ælfgifu's Swegn and Harold Harefoot. By Cnut, Emma had a third son, Harthacnut, and a daughter Gunnhildr, reducing Æthelred's sons, who were again in exile in Normandy, to little more than pawns. When Cnut died in November 1035, Harthacnut was ruling in Denmark. Emma pressed for his succession, not Edward's, claiming that in 1017 Cnut had sworn an oath that he would "never set up the son of any other woman to rule after him(3) When Emma had become Æthelred's second wife, she allegedly secured a similar promise, proclaiming that her sons, and not those of his first marriage, would succeed; if true, this would be a shrewd move, indicating Emma's astute grasp of political manoeuvring. Emma was, in both of her marriage situations, a second wife intending to gain precedence for her sons over any older, half brothers. Emma did not claim Cnut's first marriage to be unlawful, but cast doubts on whether he had sired Harold Harefoot. In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle; "Harold said that he was the son of Cnut and Ælfgifu of Northampton, but there was no truth in it.(4) She chose her youngest son to follow Cnut, for such a son had better chance of success, and she probably calculated that being younger, he would be more amenable to her wishes and advice. Harthacnut would retain for her, as king of England and Denmark, her wealth and status. Having allied herself with the Danish dynasty through marriage to Cnut, it was doubtful that regard for her position would be forthcoming from Edward and Alfred. As a practical reason behind her planning, Harthacnut would be more likely to receive support from the Angle-Danish aristocracy who had risen to considerable power under Cnut. Her main ally proved to be Earl Godwine of Wessex. Godwine, whose wife was Danish, and men like him, would prefer to secure a stable future under the continuation of the strength of the Danish dynasty, rather than attempt to restore a son of Æthelred, a weak king. When Edward and Alfred arrived in England in 1036 to make a claim for the throne, there was virtually no support for either brother. 3) Encomium Emmae Reginae ed. A. Campbell p.33 4) P. Stafford: p.163 Page 4 Neither did Emma support their attempts to claim their inheritance, attempts in which Alfred met a cruel death. The author of the Encomium Emmae Reginae, claims that a letter sent by Emma to summon her two sons by Æthelred to England, was a forgery; that it was a deliberate lure by Harold Harefoot. Godwine was implicated in this horrendous death, although he strongly denied the charges right up until his death in 1053. He intercepted Alfred's arrival in England and arrested him, the Encomium claims that Harold then took Alfred out of Godwine's control and tortured him by blinding him, wounds that were so terrible, the unfortunate young man died. One version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, C, firmly lays blame with Godwine. Florence, agrees, D suppresses his name and E has no entry for this date, 1036. It is quite possible that Emma did call her sons to England. Edward would have been in his early thirties, and her position and support for Harthacnut were rapidly crumbling. The author of the Encomium defends Emma against criticism that she had failed to die with Alfred, "since it would have appeared wrong ..... if a matron of such reputation had died for worldly power"(5) Edward, in the Encomium, discounts his own claims of succession in favour of Harthacnut. The author leaves us uncertain how Emma reacted to each of her sons between the period of 1035 and 1037: a source that suppresses the marriage that introduced Emma into England, and blatantly denies the paternity of a future king, more than twists the truth. There is no doubt regarding Emma's involvement in the matter of the succession, however, nor the depth of importance that she herself attached to it. Emma was a woman of considerable wealth and because of that, held great political power. On Cnut's death, she retained possession of the royal treasury. By 1002, the towns of Winchester and Exeter automatically formed part of the dowry of English queens, held until their death or disgrace. Emma held three types of property which would provide her with revenue; dowry lands which returned to the royal estate upon her death; a share in the revenue from the royal demesne, which would effectively provide for her household, and properties acquired through grant or gift, with rights of free disposal. As with Cnut when he had become king, the possession of the royal treasury was crucial. It would contain essential royal documents, such as tribute lists, gold, silver, precious stones and weapons. Possibly also, the royal insignia. By taking control of the treasury, Emma was able to attract - and hold - support. She, with allies such as Godwine, continued to struggle against Harold Harefoot's claims to the throne for two years after Cnut's death, a clear indication of her strength and solid determination. Harthacnut, however, was forced to remain occupied in Denmark. Godwine was the crux of Emma's success, and when he unexpectedly switched sides to support Harold Harefoot, she fell swiftly from power. 5) P. Stafford p.5 Page 5 Her choice of her youngest son had been astute, but the consequence of events outmanoeuvred her intentions. With her cause lost she fled into exile to Flanders, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, "Ælfgifu," the English form of Emma, "was driven out with no gentleness of heart in the raging winter." (6) Her own version in the Encomium states that she diplomatically withdrew. In 1039, Harthacnut joined his mother at Bruges. Harold Harefoot's death in the same year gave him opportunity to renew his claim on England. It may have been during her exile that Emma commissioned the Encomium Emmae Regina to be written, possibly by a Flemish monk.(7) It is a work of praise for herself, and is a simultaneous demonstration that Harthacnut had been the right choice to become king of England. The Encomium claims that Cnut had promised the English throne to Harthacnut, and the author completely, and skillfully, suppresses Emma's first marriage to Æthelred. Her sons by that marriage, Edward and Alfred, are shown as sons of Cnut. The Encomium shows that Queen Emma, and similarly, her daughter-in-law Edith, who later commissioned a work about Edward, were not merely literate, but women of distinguished learning. Such splendid books would be valueless to women who could not personally read and comprehend them. A modern quote emphasizes this point; when the model Naomi Campbell wrote a novel in conjunction with a "ghost writer", she was asked what the story was about, her reply "I don't know, I have not read it yet," was extensively self-demeaning. To have gained from commissioning the Encomium, Emma must have been able to fully appreciate its content. The Encomium Emmae was commissioned by Emma while she was a living queen, she wished her own voice to be heard, her viewpoint and intentions to be seen. It clearly reveals her driving determination to control the succession to the throne of England, and is a biography that intends to establish her respectability and justify her actions. Emma was a woman who, in 1041, was coming close to loosing everything she had. The writer skillfully creates her as a woman of integrity, a loyal wife, and a caring mother: there is no hint of any bad behaviour towards her sons, especially in the matter of Alfred's death. Unlike Edith however, who was depicted as modest and chaste, Emma never managed to acquire a level of saintliness. After his accession, Harthacnut invited his half brother to England. Edward remained at court until Harthacnut died. It is plausible that a family settlement was agreed while Emma was in exile in Bruges. Their strength would be increased if differences were set aside and the reward shared. The idea seems more likely to have been Harthacnut's rather than Emma's, for in the Encomium, she determines that Harthacnut's claim to the throne was stronger than Edward's and that his provision for Edward was out of brotherly love. 6) The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles: trans. Anne Savage 7) P. Stafford Page 6 William of Poitiers, writing much later, gives a different explanation, saying that Harthacnut knew he was a dying man - a view easily surmised with hindsight. The renewal of family togetherness was the regrouping of a family desperately needing to reinstate itself. Actions dictated by necessity, not love. Harthacnut's reign was brief. We can only guess at the extent of Emma's grief at his death in 1042. After all her struggles, with her hopes and expectant ambition, she must have been devastated. The crown passed to her eldest born son, Edward, but events proved this to be of little comfort to her. For most of his life Edward had lived in exile in Normandy. His mother had abandoned him to marry the man who had ousted his father, and had, so rumour said, been involved with the killing of his brother. There was no love between son and mother. Soon after his consecration in November 1043, Edward, accompanied by his earls, rode to Winchester to accuse Emma of treason, and to dispossess her of her lands and movables, although he stopped short at outlawry or exile. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, "they came unexpectedly upon the lady and deprived her of all the treasures which she owned and which were beyond counting, because she had been very hard to the king, her son, in that she did less for him than he wished both before he became king and afterwards as well. (8) It is possible that Emma had been determined to continue in her previous vein by continuing to exercise her Queen's rights - she had undoubtedly been regent of England while Cnut had been abroad, and had been a guiding hand to Harthacnut. Edward may not have accepted her interferences with government. Emma's confidant, Stigand, was appointed bishop of East Anglia soon after Edward's consecration, probably appointed by Emma herself, one "straw too many" that pushed Edward beyond endurance. He deposed Stigand, confiscating all his possessions, "because he was closest to his mother's council". (9) Edward also granted an estate at Mildenhall, that had been Emma's, to Bury St Edmunds, and the eight and a half hundreds relating to Thingoe, Suffolk, in her possession. These were returned to her, for at her death, Edward regranted them to the abbey. Whether by her own strength of character or her son's remorse, she was soon reinstated into favour, although at a lower scale. Stigand was restored in 1044. Styled as the king's mother, Emma regularly witnessed charters until her son's marriage, either those who drafted the documents ignored her fall, or it was too brief a period to be noticed. A queen mother, especially one of learning and with a leaning towards continuing her own status, could hold extensive influence over a son. As a means of satisfying personal revenge, queens as stepmothers or mothers-in-law, could, if they so wished, create numerous problems for their sons. 8) H. Leyser: Medieval Women p.80 9) Chron. C Page 7 Æthelred did not marry Emma until his mother had retired to Wherwell Abbey, possibly even after she had died. She had dominated the early part of his reign, and Emma was equally as prominent at Harthacnut's side during his brief kingship. When Edward married Earl Godwine's daughter Edith however, Emma retired to Winchester, an indication that her influence at court, and her domination over her son, had decreased. Emma died on 6th March 1052. She was buried in the Old Minster, Winchester near Cnut and Harthacnut. It is regrettable that later queens of England are discussed at length, appreciated or condemned, depending on their worth, while the known queens of pre-Norman history are considerably neglected - even ignored. I believe I am correct in saying that Emma was the only woman in British history to have been Queen twice, the wife of different ruling Kings. This makes her unique. Emma was an intriguing woman, on a par with the later Eleanor of Aquitaine. Emma's only detriment; there is little documented, independent evidence of her life and character. For all that, she has a significant place in English history.

Sources: Pauline Stafford Queens, concubines and Dowagers: The king's wife in the early middle ages Batsford Academic Henrietta Leyser Medieval Women: A social history of women in England 450- 1500 Weidenfeld & Nicolson Christine Fell Women in Anglo-Saxon England Colonnade (British Museum Publications) Frank Barlow Edward the Confessor Eyre & Spottiswode Translator, Anne Savage: The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles William Heinemann Ltd Assessment "This is an excellent essay, your enjoyment in writing it is clear. It is ironic that Emma, the first English queen known to have written (or commissioned) her story, showing an awareness of history as important, should have been so neglected. She lived to be 60, not a bad age in the period, which shows a remarkable constitution! I particularly like your use of primary sources." 80% 10.3.1997 J Mountain B.A. B.Sc. Note: I went on to write my full thesis on Queen Emma, giving a more detailed account of this remarkable woman's life.    |

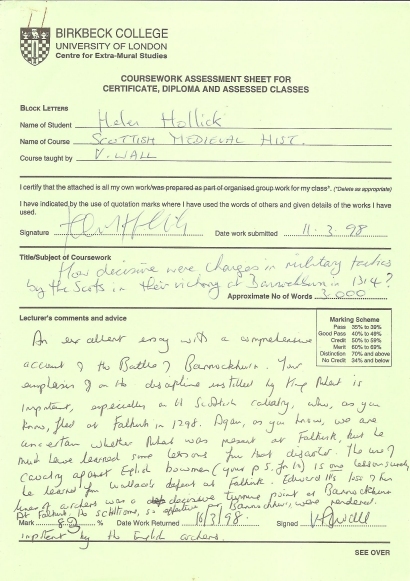

"How decisive were changes in military tactics by the Scots in their victory at

This is an essay, written in 1998 during a history degree course at Birkbeck College, University of London. Bannockburn in 1314?" |

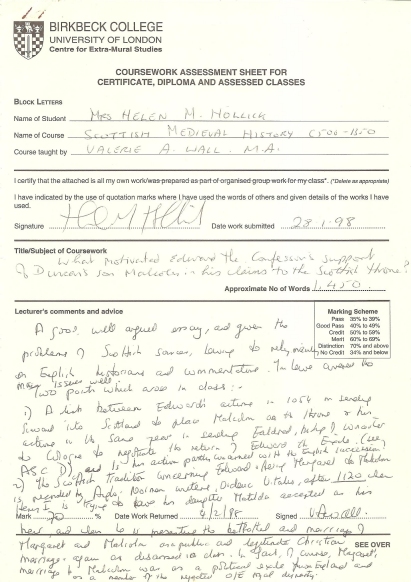

"What motivated Edward the Confessor's support of Duncan's son Malcolm

This is an essay, written in 1998 during a history degree course at Birkbeck College, University of London. in his claims to the Scottish throne?" |

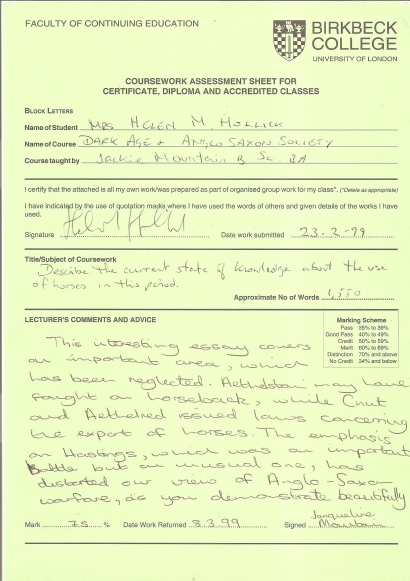

"Describe the current state of knowledge about the use of horses in this period."

This is an essay, written in 1999 during a history degree course at Birkbeck College, University of London. |

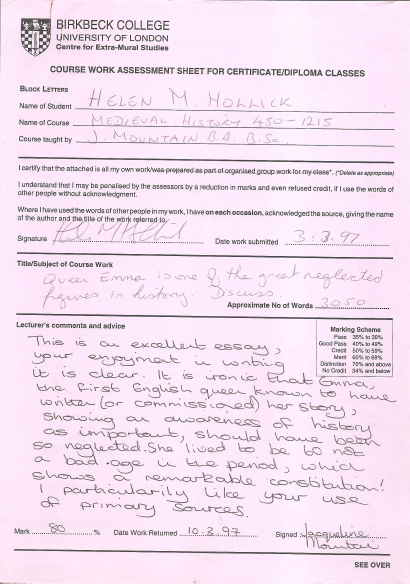

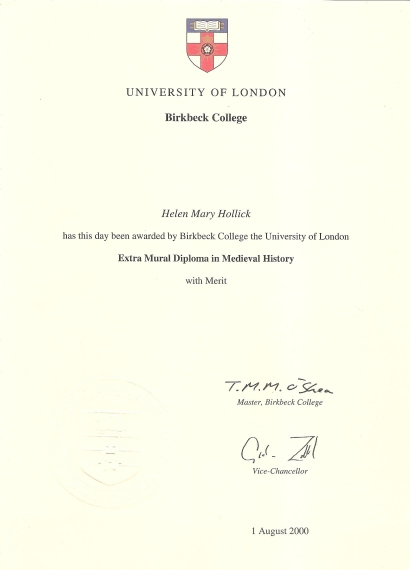

| Extra Mural Certificate: A Distinction was awarded in 1999 on the basis of these essays. Extra Mural Diploma: I graduated the course in 2000 with Merit. |

"Harold the King"

"Harold the King" "I Am The Chosen King"

"I Am The Chosen King"